When eight companies turned up to pitch their elephant- detection technology for railway tracks in February, officials in Jharkhand’s Chakradharpur division were left scratching their heads. How will they get two elephants for the trial?

Over the next four months, they fired off letter after letter—to forest departments, zoos in Jamshedpur and Ranchi and even a private agency in distant Bhopal—almost pleading them to loan elephants. Relief finally came from a temple trust linked to the Reliance Group’s Vantara, which dispatched two elephants from Deoria in Uttar Pradesh. The animals were ferried all the way to Chakradharpur in a specially built animal ambulance.

“We needed elephants for the trial, as the signature of footsteps from another animal would be completely different,” says Tarun Huria, divisional railway manager, Chakradharpur. “We conducted multiple trials—of elephants stepping onto the track, moving away from it, walking parallel and even simulated herd movements. Finally, we zeroed in on the right supplier for the Elephant Intrusion Detection System (EIDS), which can pick up elephant movements at least 20 metres from the opticalfibre cable along the tracks.”

In designated elephant corridors, the system will track and display continuous elephant movements from as far as 150-200 metres from the centre of the track. Huria adds that the same technology could later be adapted to track other animals, say, camels straying too close to railway lines in Rajasthan.

MAMMOTH TASK AHEAD

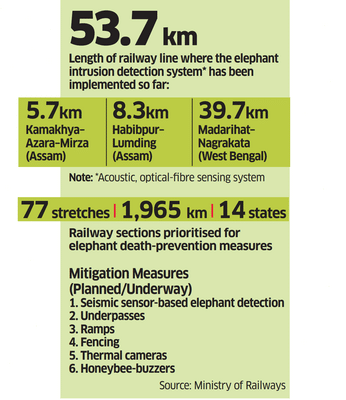

Every year, more than a dozen elephants get killed on India’s railway tracks, and many more are left injured by speeding trains. The government is now racing to protect the animal with a mix of new technologies such as EIDS and thermal cameras alongside conventional measures like wildlife underpasses, bridges for elephants, ramps and fencing. And in a quirky twist, honeybee-buzzer devices have been installed at some level crossings to repel elephants and steer them away from the tracks.

India is home to 29,964 elephants, according to the last nationwide census conducted in 2017. But their habitats are shrinking fast. Highways, expressways and the relentless doubling and tripling of railway tracks are slicing through forest corridors, pushing elephants into often fatal collisions with trains. The Indian Railways’ drive to raise train speeds, along with the arrival of semi-highspeed services like the Vande Bharat, has only heightened the risk.

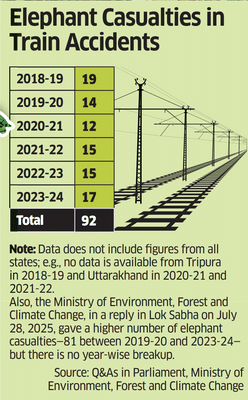

Government records show at least 92 elephants were killed in train collisions between 2018-19 and 2023-24. The real toll is almost certainly higher as some deaths go unreported. In a written reply to the Lok Sabha on July 28, 2025, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) acknowledged 81 casualties from 2019-20 to 2023-24, though it did not share a year-wise breakup. Also, the number of injured elephants hit by trains is not readily available.

A 2024 report, “Handbook to Mitigate the Impacts of Roads and Railways on Asian Elephants”, published by the Asian Elephant Transport Working Group, reveals the magnitude of the crisis: 355 elephants died in train collisions in India between 1987 and April 2023, nearly two-thirds of them in just two states, Assam and West Bengal. “Trainelephant collisions were found to occur more often at night and involved more male elephants when accounted for in terms of ratio in the population, as males may cross the tracks more often to embark on crop raiding behaviour during crop harvest season,” the report says.

A March 2025 report by MoEF&CC and the Wildlife Institute of India has recommended mitigation measures for 77 railway stretches covering 1,965 km across 14 states. The plan calls for 705 new structures: 503 ramps and level crossings, 72 bridge extensions or modifications, 39 fencing, barricades or trenches, 4 exit ramps, 65 underpasses and 22 overpasses. The planning for some of these has already begun.

EXPRESS THROUGH ELEPHANT CORRIDOR

Last week, this writer boarded the Ispat Express, a superfast train that cuts through some of the most vulnerable elephant corridors on the Jharkhand-Odisha border, to witness first-hand the dilemma faced by loco pilots navigating these habitats.

“We take extra caution in elephant corridors,” says RN Gudu, 55, the train’s loco pilot. “On certain stretches — for example, between Jaraikela and Manoharpur on Jharkhand-Odisha border—we are instructed to slow trains to 40 kmph from 6 pm to 6 am. Even the Vande Bharat driver must comply with this rule.”

Another loco pilot, Abhimanyu Singh, who drives the South Bihar Express on the same route, says: “In daylight you can scan the surroundings, but at night you see only about 150-200 metres of track ahead.”

WARNING SYSTEM

According to the Tamil Nadu forest department records, nearly 9,000 elephant crossings were logged in the Madukkarai forest range in Coimbatore, near the Kerala border, between 2021 and 2023. With around 300 trains passing through these elephant corridors daily, the risk is constant. Alarm bells rang in 2021, when three female elephants were killed by trains in the Madukkarai-Coimbatore stretch.

“The state forest department launched an AI-powered surveillance project in February 2024, installing thermal and regular cameras on 12 towers along a critical 7 km stretch in Madukkarai,” says Supriya Sahu, additional chief secretary, Environment, Climate Change & Forests Department, Tamil Nadu. “Last year alone, there were 342 instances when elephants were spotted on the tracks and drivers were alerted in time, significantly reducing collisions.”

She adds that the department now plans to replicate and extend this early-warning system to other critical elephant and wildlife corridors. Future upgrades may include integration with drone surveillance and wider use of advanced tools such as geophones, fibre-based sensing and radar systems.

Meanwhile, the North East Frontier Railway has rolled out an AI-enabled intrusion detection system, also called DAS (Distributed Acoustic Sensors), across 53.7 km of track—39.7 km in West Bengal and 14 km in Assam. The system detects elephant movement near the tracks and instantly alerts loco pilots, station masters and control rooms, enabling timely preventive action.

Railway documents show that work is now underway to expand the technology across 147 km of elephant corridors—70 km in Assam and 77 km in West Bengal. In all, this sensor-based system has been sanctioned for 1,158 km of railway lines, at an estimated cost of `208 crore, according to information tabled in the Rajya Sabha last month.

ARE HATHI PASSES WORKING?

While the effectiveness of many new-age technologies is still untested, this is also the time for Indian Railways to take stock of its existing measures—bridges and underpasses built over the past decade exclusively for elephants and other wildlife—and assess how well they are working. In many places, existing mitigation measures need urgent upgrades such as better barricading and installation of light and sound barriers.

In 2015, two hathi passes—grass-covered wildlife bridges for elephants—were constructed in the forests of Hazaribagh in Jharkhand, as a new railway line from Koderma to Hazaribagh cut through hillocks along traditional elephant corridors. A decade on, the elephants have all but abandoned this habitat.

Last week, a drive on a long, winding rural road and a kilometre’s walk through the forest-fringed village of Barikola Jhonjh led us to a hathi pass. In the fading light, an old woman was herding home two dozen cows, goats and sheep—using the hathi pass. The animals seemed at home; the bridge was serving them well. But the giants it was built for were nowhere in sight.

“From the time this bridge was built, elephants have stopped coming here,” says villager Binod Munda with a wry smile.

In a 55-km stretch in Odisha under the Chakradharpur railway division, 11 new hathi passes have been recently sanctioned, with the government setting aside `234 crore for the project. Similar bridges are on the drawing board in Jharkhand and other states.

But has anything been learnt from Hazaribagh’s abandoned overpass in Munda’s village? Officials insist the new generation of bridges will be different. “They are being designed to actively draw elephants in,” says a Chakradharpur official, who is drafting the budget for them. “The plans even include planting jackfruit and banana trees to entice the herds.” Will the elephants bite?

Over the next four months, they fired off letter after letter—to forest departments, zoos in Jamshedpur and Ranchi and even a private agency in distant Bhopal—almost pleading them to loan elephants. Relief finally came from a temple trust linked to the Reliance Group’s Vantara, which dispatched two elephants from Deoria in Uttar Pradesh. The animals were ferried all the way to Chakradharpur in a specially built animal ambulance.

“We needed elephants for the trial, as the signature of footsteps from another animal would be completely different,” says Tarun Huria, divisional railway manager, Chakradharpur. “We conducted multiple trials—of elephants stepping onto the track, moving away from it, walking parallel and even simulated herd movements. Finally, we zeroed in on the right supplier for the Elephant Intrusion Detection System (EIDS), which can pick up elephant movements at least 20 metres from the opticalfibre cable along the tracks.”

In designated elephant corridors, the system will track and display continuous elephant movements from as far as 150-200 metres from the centre of the track. Huria adds that the same technology could later be adapted to track other animals, say, camels straying too close to railway lines in Rajasthan.

MAMMOTH TASK AHEAD

Every year, more than a dozen elephants get killed on India’s railway tracks, and many more are left injured by speeding trains. The government is now racing to protect the animal with a mix of new technologies such as EIDS and thermal cameras alongside conventional measures like wildlife underpasses, bridges for elephants, ramps and fencing. And in a quirky twist, honeybee-buzzer devices have been installed at some level crossings to repel elephants and steer them away from the tracks.

India is home to 29,964 elephants, according to the last nationwide census conducted in 2017. But their habitats are shrinking fast. Highways, expressways and the relentless doubling and tripling of railway tracks are slicing through forest corridors, pushing elephants into often fatal collisions with trains. The Indian Railways’ drive to raise train speeds, along with the arrival of semi-highspeed services like the Vande Bharat, has only heightened the risk.

Government records show at least 92 elephants were killed in train collisions between 2018-19 and 2023-24. The real toll is almost certainly higher as some deaths go unreported. In a written reply to the Lok Sabha on July 28, 2025, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) acknowledged 81 casualties from 2019-20 to 2023-24, though it did not share a year-wise breakup. Also, the number of injured elephants hit by trains is not readily available.

A 2024 report, “Handbook to Mitigate the Impacts of Roads and Railways on Asian Elephants”, published by the Asian Elephant Transport Working Group, reveals the magnitude of the crisis: 355 elephants died in train collisions in India between 1987 and April 2023, nearly two-thirds of them in just two states, Assam and West Bengal. “Trainelephant collisions were found to occur more often at night and involved more male elephants when accounted for in terms of ratio in the population, as males may cross the tracks more often to embark on crop raiding behaviour during crop harvest season,” the report says.

A March 2025 report by MoEF&CC and the Wildlife Institute of India has recommended mitigation measures for 77 railway stretches covering 1,965 km across 14 states. The plan calls for 705 new structures: 503 ramps and level crossings, 72 bridge extensions or modifications, 39 fencing, barricades or trenches, 4 exit ramps, 65 underpasses and 22 overpasses. The planning for some of these has already begun.

EXPRESS THROUGH ELEPHANT CORRIDOR

Last week, this writer boarded the Ispat Express, a superfast train that cuts through some of the most vulnerable elephant corridors on the Jharkhand-Odisha border, to witness first-hand the dilemma faced by loco pilots navigating these habitats.

“We take extra caution in elephant corridors,” says RN Gudu, 55, the train’s loco pilot. “On certain stretches — for example, between Jaraikela and Manoharpur on Jharkhand-Odisha border—we are instructed to slow trains to 40 kmph from 6 pm to 6 am. Even the Vande Bharat driver must comply with this rule.”

Another loco pilot, Abhimanyu Singh, who drives the South Bihar Express on the same route, says: “In daylight you can scan the surroundings, but at night you see only about 150-200 metres of track ahead.”

WARNING SYSTEM

According to the Tamil Nadu forest department records, nearly 9,000 elephant crossings were logged in the Madukkarai forest range in Coimbatore, near the Kerala border, between 2021 and 2023. With around 300 trains passing through these elephant corridors daily, the risk is constant. Alarm bells rang in 2021, when three female elephants were killed by trains in the Madukkarai-Coimbatore stretch.

“The state forest department launched an AI-powered surveillance project in February 2024, installing thermal and regular cameras on 12 towers along a critical 7 km stretch in Madukkarai,” says Supriya Sahu, additional chief secretary, Environment, Climate Change & Forests Department, Tamil Nadu. “Last year alone, there were 342 instances when elephants were spotted on the tracks and drivers were alerted in time, significantly reducing collisions.”

She adds that the department now plans to replicate and extend this early-warning system to other critical elephant and wildlife corridors. Future upgrades may include integration with drone surveillance and wider use of advanced tools such as geophones, fibre-based sensing and radar systems.

Meanwhile, the North East Frontier Railway has rolled out an AI-enabled intrusion detection system, also called DAS (Distributed Acoustic Sensors), across 53.7 km of track—39.7 km in West Bengal and 14 km in Assam. The system detects elephant movement near the tracks and instantly alerts loco pilots, station masters and control rooms, enabling timely preventive action.

Railway documents show that work is now underway to expand the technology across 147 km of elephant corridors—70 km in Assam and 77 km in West Bengal. In all, this sensor-based system has been sanctioned for 1,158 km of railway lines, at an estimated cost of `208 crore, according to information tabled in the Rajya Sabha last month.

ARE HATHI PASSES WORKING?

While the effectiveness of many new-age technologies is still untested, this is also the time for Indian Railways to take stock of its existing measures—bridges and underpasses built over the past decade exclusively for elephants and other wildlife—and assess how well they are working. In many places, existing mitigation measures need urgent upgrades such as better barricading and installation of light and sound barriers.

In 2015, two hathi passes—grass-covered wildlife bridges for elephants—were constructed in the forests of Hazaribagh in Jharkhand, as a new railway line from Koderma to Hazaribagh cut through hillocks along traditional elephant corridors. A decade on, the elephants have all but abandoned this habitat.

Last week, a drive on a long, winding rural road and a kilometre’s walk through the forest-fringed village of Barikola Jhonjh led us to a hathi pass. In the fading light, an old woman was herding home two dozen cows, goats and sheep—using the hathi pass. The animals seemed at home; the bridge was serving them well. But the giants it was built for were nowhere in sight.

“From the time this bridge was built, elephants have stopped coming here,” says villager Binod Munda with a wry smile.

In a 55-km stretch in Odisha under the Chakradharpur railway division, 11 new hathi passes have been recently sanctioned, with the government setting aside `234 crore for the project. Similar bridges are on the drawing board in Jharkhand and other states.

But has anything been learnt from Hazaribagh’s abandoned overpass in Munda’s village? Officials insist the new generation of bridges will be different. “They are being designed to actively draw elephants in,” says a Chakradharpur official, who is drafting the budget for them. “The plans even include planting jackfruit and banana trees to entice the herds.” Will the elephants bite?

You may also like

"Every time in 'Mann Ki Baat' program, something new happens": UP Dy CM Brajesh Pathak

Jeff Brazier breaks silence after Freddy's baby news as he's to become granddad at 47

Is new normal to be defined by Chinese aggression and bullying: Congress

India's horticulture output leaps to 367.72 million tonnes

Voter Adhikar Yatra to end with Patna march on Monday